The Silver Crisis: When Paper Systems Begin to Fail

In December, the precious metals market saw silver—not gold—take center stage as the brightest performer.

Silver rocketed from $40 to $50, then $55, and $60, breaking through one historic price level after another at a near-unchecked pace, leaving little room for the market to catch its breath.

On December 12, spot silver briefly reached a record high of $64.28 per ounce before sharply reversing course. Year to date, silver has surged nearly 110%, far outstripping gold’s 60% gain.

This rally may appear “perfectly rational,” but that very rationality makes it especially perilous.

The Crisis Behind the Rally

Why is silver rallying?

Because it seems to deserve it.

By mainstream institutional logic, all the pieces fit.

The Federal Reserve’s renewed rate-cut expectations have reignited interest in precious metals. Recent soft employment and inflation data have the market betting on further rate cuts in early 2026. As a highly responsive asset, silver reacts even more sharply than gold.

Industrial demand is also fueling the surge. Explosive growth in solar power, electric vehicles, data centers, and AI infrastructure has highlighted silver’s dual role as both a precious and industrial metal.

Global inventories continue to decline, compounding the pressure. Fourth-quarter mine production in Mexico and Peru missed forecasts, and major exchange warehouses have seen silver bar stocks dwindle year after year.

On these grounds alone, silver’s rally seems like a market “consensus”—even a long-overdue revaluation.

But the real risk lies beneath the surface:

Silver’s ascent may look justified, but it’s far from secure.

The core issue is simple—silver isn’t gold. It lacks gold’s universal consensus and the backing of “national teams.”

Gold’s resilience comes from central banks worldwide buying aggressively. Over the past three years, central banks have acquired more than 2,300 tons of gold, adding it to their balance sheets as an extension of sovereign credit.

Silver is a different story. While central bank gold reserves exceed 36,000 tons globally, official silver reserves are virtually nonexistent. Without a central bank backstop, silver lacks any systemic stabilizer during extreme volatility, making it a classic “orphan asset.”

The gap in market depth is even wider. Gold’s daily trading volume is about $150 billion, compared to just $5 billion for silver. If gold is the Pacific Ocean, silver is little more than a lake.

Silver’s market is small, with limited market makers, thin liquidity, and restricted physical reserves. Most importantly, the primary way to trade silver isn’t physical—it’s “paper silver”: futures, derivatives, and ETFs dominate the market.

This structure is fraught with risk.

In shallow markets, large capital inflows can quickly roil the entire surface.

This year, that’s exactly what happened: a sudden wave of capital entered, rapidly propelling prices in a market with little depth and sending them skyward.

Futures Short Squeeze

What truly drove silver prices off course wasn’t the seemingly logical fundamentals—it was a price war in the futures market.

Normally, spot silver prices trade at a slight premium to futures. This makes sense: holding physical silver incurs storage and insurance costs, while futures are just contracts—hence cheaper. This difference is called the “spot premium.”

But starting in Q3 this year, that logic flipped.

Futures prices began trading systematically above spot, and the gap kept widening. What does that signal?

Someone is aggressively bidding up futures prices. This “futures premium” typically appears in two scenarios: either the market is extremely bullish on the future, or someone is orchestrating a short squeeze.

Given that silver’s fundamentals are improving only gradually—solar and new energy demand won’t explode in months, and mine supply won’t vanish overnight—the aggressive futures action looks much more like the latter: capital is driving up futures prices.

Even more concerning are the anomalies in the physical delivery market.

Historical data from COMEX, the world’s largest precious metals exchange, shows that less than 2% of precious metals futures contracts settle via physical delivery; the other 98% are closed out in cash or rolled forward.

Yet in recent months, physical silver deliveries on COMEX have soared, far above historical averages. More investors are losing faith in “paper silver” and demanding real silver bars.

Similar patterns have emerged in silver ETFs. While large inflows continue, some investors are redeeming shares for physical silver rather than fund units. This “run-like” redemption is putting pressure on ETF silver reserves.

This year, all three major silver markets—New York’s COMEX, London’s LBMA, and the Shanghai Metal Exchange—have experienced redemption waves.

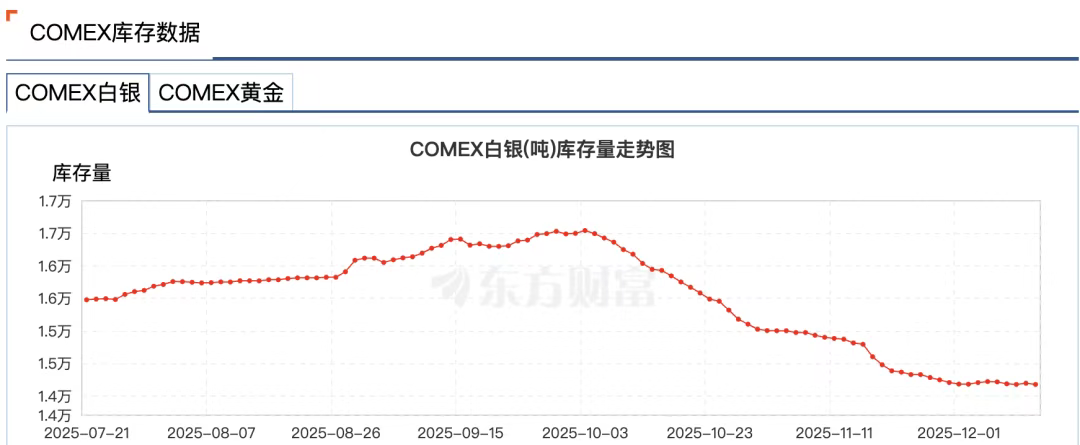

Wind data shows that during the week of November 24, silver inventories at the Shanghai Gold Exchange dropped by 58.83 tons to 715.875 tons—the lowest since July 3, 2016. COMEX silver stocks plunged from 16,500 tons in early October to 14,100 tons, a 14% decline.

The reason is clear: in a US dollar rate-cut cycle, investors are reluctant to settle in USD. Another underlying concern is whether exchanges can actually deliver enough physical silver.

The modern precious metals market is highly financialized. Most “silver” exists as book entries, while real silver bars are repeatedly pledged, lent, and used in derivatives worldwide. A single ounce of physical silver might underpin a dozen different claims simultaneously.

Veteran trader Andy Schectman notes that, for example, the LBMA in London has just 140 million ounces of floating supply, while daily trading volume hits 600 million ounces—and more than 2 billion ounces of paper claims exist on those 140 million ounces.

This “fractional reserve” system works under normal conditions, but if everyone demands physical delivery, the system faces a liquidity crisis.

When crisis looms, financial markets often see a peculiar phenomenon—what’s colloquially called “pulling the plug.”

On November 28, CME suffered an outage lasting nearly 11 hours due to “data center cooling issues”—its longest ever—halting COMEX gold and silver futures updates.

Notably, the outage occurred just as silver was breaking historic highs. Spot silver breached $56, and silver futures broke $57 that day.

Market rumors suggested the outage was intended to protect commodity market makers exposed to extreme risks and potential massive losses.

Subsequently, data center operator CyrusOne attributed the disruption to human error, fueling even more conspiracy theories.

In short, a rally driven by futures short squeezes has made silver exceptionally volatile. Silver has effectively shifted from a traditional safe haven to a high-risk asset.

Who’s Pulling the Strings?

In this short squeeze saga, one name is inescapable: JPMorgan Chase.

The reason is simple: JPMorgan is globally recognized as the dominant force in the silver market.

From at least 2008 to 2016, JPMorgan traders manipulated gold and silver prices.

The methods were blunt: placing large buy or sell orders for silver futures to create false supply and demand, luring others in, then canceling the orders at the last second to profit from price swings.

This practice, known as spoofing, led to a $920 million fine for JPMorgan in 2020—a record single penalty from the CFTC.

But true textbook market manipulation goes deeper.

JPMorgan used large-scale short selling and spoofing in the futures market to suppress silver prices, then accumulated physical metal at those depressed prices.

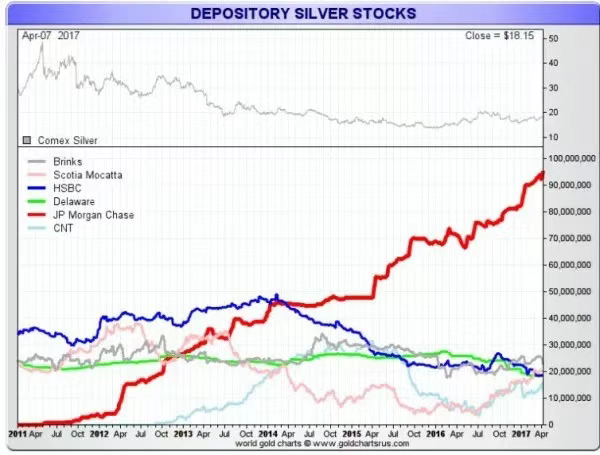

From the 2011 silver high near $50, JPMorgan started stockpiling silver in its COMEX warehouse, increasing holdings even as other major institutions cut back—at one point holding up to 50% of total COMEX silver stocks.

This strategy exploited structural flaws in the silver market: paper silver prices drive physical prices, and JPMorgan can influence both while remaining one of the largest physical holders.

So, what role is JPMorgan playing in the current silver short squeeze?

On the surface, JPMorgan appears to have “turned over a new leaf.” After the 2020 settlement, it carried out sweeping compliance reforms, hiring hundreds of new compliance officers.

There’s currently no evidence JPMorgan is involved in the current squeeze, but its influence over the silver market remains immense.

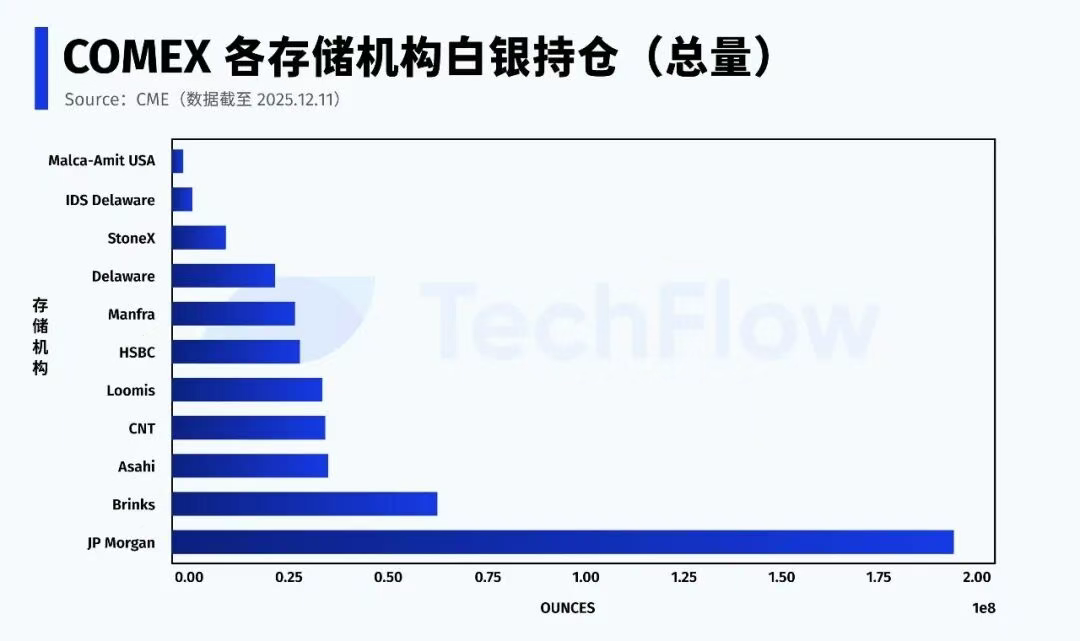

According to CME data from December 11, JPMorgan holds about 196 million ounces of silver (proprietary plus brokerage) within the COMEX system—nearly 43% of total exchange stocks.

JPMorgan is also the custodian for the silver ETF (SLV). As of November 2025, it held 517 million ounces of silver valued at $32.1 billion.

Crucially, for “Eligible” silver (deliverable but not yet registered), JPMorgan controls more than half the total volume.

In any short squeeze, the real contest boils down to two questions: who can provide physical silver, and whether (and when) that silver is allowed into the delivery pool.

Unlike its former role as a major silver short, JPMorgan now sits at the “silver gate.”

Currently, Registered silver available for delivery is only about 30% of total stocks. When most Eligible silver is concentrated among a few institutions, the stability of the silver futures market ultimately depends on the choices of a handful of key players.

The Paper System Is Breaking Down

If you had to sum up today’s silver market in a single phrase, it would be this:

The rally continues, but the rules have changed.

The market has undergone an irreversible transformation—trust in the “paper system” for silver is eroding.

Silver isn’t unique; the gold market is seeing the same shift.

Gold inventories at the New York futures exchange keep shrinking. Registered gold stocks have repeatedly hit lows, forcing the exchange to reallocate bars from “Eligible” reserves not originally intended for delivery.

Globally, capital is quietly migrating.

For over a decade, mainstream asset allocations were highly financialized—ETFs, derivatives, structured products, leverage—everything could be securitized.

Now, more capital is flowing out of financial assets and into physical assets that don’t rely on financial intermediaries or credit guarantees—gold and silver above all.

Central banks are steadily and substantially increasing their gold reserves, almost exclusively in physical form. Russia has banned gold exports, and even Western countries like Germany and the Netherlands are demanding the repatriation of gold held overseas.

Certainty is now trumping liquidity.

When gold supply can’t meet surging physical demand, capital seeks alternatives—making silver the natural first choice.

This shift toward physical assets is, at its core, a contest for monetary pricing power in a world of a weakening dollar and deglobalization.

According to Bloomberg’s October report, global gold flows are shifting from West to East.

Data from the US CME and London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) show that since late April, over 527 tons of gold have left New York and London vaults—the West’s two largest markets—while gold imports by major Asian consumers like China have soared. In August, China’s gold imports hit a four-year high.

In response, by the end of November 2025, JPMorgan will relocate its precious metals trading team from the US to Singapore.

The surge in gold and silver prices signals a return to the “gold standard” mindset. While a full return may be unrealistic in the short term, one thing is certain: those who control more physical metal hold greater pricing power.

When the music stops, only those holding real gold and silver will have a seat at the table.

Statement:

- This article is reprinted from [TechFlow]. Copyright belongs to the original author [Xiao Bing]. If you have any objections to this reprint, please contact the Gate Learn team, and we will address your concerns promptly according to established procedures.

- Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not constitute investment advice.

- Other language versions of this article are translated by the Gate Learn team. Do not copy, distribute, or plagiarize translated articles unless Gate is cited.

Related Articles

Gate Research: 2024 Cryptocurrency Market Review and 2025 Trend Forecast

Altseason 2025: Narrative Rotation and Capital Restructuring in an Atypical Bull Market

Detailed Analysis of the FIT21 "Financial Innovation and Technology for the 21st Century Act"

The Impact of Token Unlocking on Prices

Gate Research: Web3 Industry Funding Report - November 2024